If you were to mention Weeksville to the average non-Black New Yorker, chances are you would be met with blank looks – perhaps understandably so. Weeksville’s history stretches back almost two centuries ago to 1838, where it was envisioned as a safe haven for African Americans who wanted to live on their own terms, and build up their own community.

I’ll show the modern-day photos I took later on.

Slavery had just been abolished in New York in 1827, so there were many African Americans who lived in the South that found Weeksville appealing. The 13th Amendment (which officially abolished slavery) was only passed after the civil war ended in 1865, so New York was likely seen as very progressive at the time for many African Americans. Weeksville was also rather isolated at the time as well, as it was across the river from Manhattan (there was no bridge at the time and one had to take a boat over to Brooklyn) and it was mostly farmland and undulating low hills.

At Weeksville’s peak in the 1880s to early 1900s, more than 500 people called it home, and it was a self-sufficient community, with its own doctors, teachers and journalists. Land ownership was a key premise for voting rights in New York at the time – white men were allowed to vote regardless of whether they owned property, but for black men, they were required to own property worth at least $250 in order to be given voting rights. Therefore, Weeksville was an ideal solution – a community of landowners in which African Americans could truly be free.

However, the beginning of the end came with the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge, which opened in 1883. As Brooklyn became more accessible to those coming from Manhattan, the community of Weeksville became subsumed by the burgeoning neighbourhoods such as Bedford-Stuyvesant (now, Weeksville is considered as part of Crown Heights). Luckily, the area was designated as landmarks in 1970, and the Weeksville Heritage Center was later constructed in 2013 – which was my destination for the day.

After getting off Utica Ave station on the 4 train, I made my way through Utica Avenue and gradually reached the intersection of St. Marks Ave & Rochester Ave, which was about one block away from the Weeksville Heritage Center, which is next to the Kingsborough Housing Projects. You can see the towering 25-storey Kingsborough Housing Project Extension building in the distance in the photo.

When I reached, I was a little surprised at the grandeur of the space. From my previous experiences walking around the area, east of Utica Avenue is mostly untouched by gentrification and has remained largely the same, and the area is still prone to some sporadic gun violence, especially at night. Therefore, the Weeksville Heritage Centre looked vastly different from everything else in the surrounding area.

After greeting the lady manning the counter, I realised I seemed to be the only visitor today. This was later confirmed when I signed into the visitor logbook and saw that the previous entry was written yesterday, and anxiously enquired about whether the tour was still on. Luckily, she re-assured me that it would still go on as planned.

The space was immaculately clean and modern, and you could scarcely differentiate the Heritage Center from any other cultural sites in Manhattan when you are inside, despite the surrounding area being largely untouched by gentrification.

From here, a long, windowed corridor led to the heritage center’s function room, which looked like it could comfortably seat about 80 people. I made my way up a flight of stairs in the corner to reach their library, which was fairly spacious and well-lit.

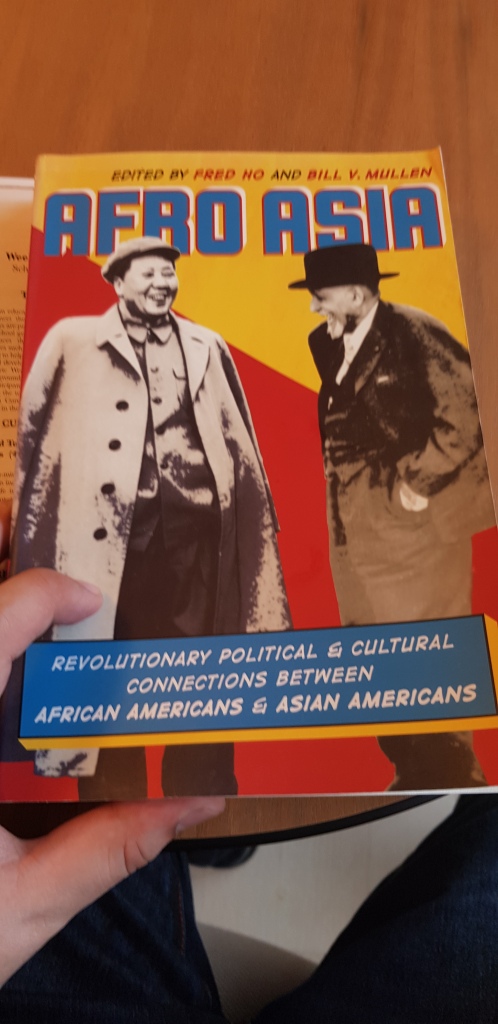

The shelves were all lined with books on African American heritage and history. One particular book caught my eye though.

I thumbed through the book fairly quickly, while reading excerpts from some chapters, but it was very fascinating, including one about how there was an Asian American lady who was very prominent in Harlem as a champion of African American rights and accepted by the community there.

Would love to get around to reading this book one day, but anecdotally, it feels like there’s more distrust between the African American and Asian American communities in more recent times. I did read about movements led by Asian Americans supporting the BLM movement, but I do not know enough to comment on whether most Asian Americans are apathetic or sympathetic to the BLM cause.

After looking through a few more books, I decided to make my way back to the registration counter for the tour, which would showcase the historic Hunterfly Road Houses shown in the first photo, that have been preserved till today.

The tour guide soon appeared, and I was the only participant for the tour. A very eloquent teenager, she gave a brief introduction about the Weeksville community and the Weeksville Heritage Center, before we headed outside to the Hunterfly Road Houses.

Each house is meant to represent a different time period, of how its inhabitants lived in that particular era. The house on the left dates back to the 1860s, the house in the middle dates back to the 1900s and the rightmost house reflected the 1930s. The following descriptions are taken from the Weeksville Society website.

1860s Historic House

A single-story, double-house that contains furniture and other artifacts relating to the mid-19th century. Visitors learn about the agrarian village of Weeksville and its inhabitants during the Civil War era. During the 1863 New York City Draft Riots, Weeksville served as a refuge for African Americans escaping the violence in Lower Manhattan. At this time, residents enjoyed a self-sufficient life, participating in a variety of occupations and developing several important community institutions.

1900s Historic House

A two-story wood framed house that was inhabited by the Johnsons, an African American family of three generations that lived here in the 1900s. Visitors explore the themes of family life in the 1900s against a backdrop of increasing community diversity and national hostility towards African Americans, as well as learning about technological advances of turn-of-the-century America.

1930s Historic House

The Williams family, who lived here from 1923 to 1968, stayed together during one of the toughest times in US history – The Great Depression. The artifacts in this house reflect those times and are based on actual furniture and objects that were owned by the Williams. The music, warmth, and stories of this family come alive during a visit to the home.

I took some photos of the artefacts in the houses – I can’t remember which photo belongs to which house. I only found out from my tour guide later on that normally photos aren’t normally allowed inside the houses, but she let things slide for these ones 🙂

I took one last 360-degree video of the area and the tour came to an end afterwards.

I chatted with the tour guide about the area afterwards, and she expressed some surprise when I said I’ve been in the area before and some amazement that I’d even been to Brownsville before. I also told her I’m actually from Singapore and she said she’d watched Crazy Rich Asians and asked how it was like here.

On hindsight, I probably burst her bubble a little too much when I said around 80% of Singaporeans live in public housing (housing projects in NYC are usually run-down and in disrepair) and that the movie blew things out of proportion, with the film showing many locations in Malaysia as well. She seemed a little disappointed afterwards – oops. Even so, she warmly welcomed me to return for future events, and that the Weeksville Heritage Center does events fairly regularly.

After we bade goodbye, I emerged into the cold, crisp January air in Crown Heights once more. Thinking about my next steps for the day, I then decided (on a whim) to make another visit to Brownsville – this time, to check the numerous murals and street art around the area. As Crown Heights borders the western boundary of Brownsville, it would only be about a 15 minute walk to reach there.

In my next post, I will showcase some of the mural photos I took and discuss the Brownsville neighbourhood more.